Trade Tariffs

Consequences of Trade Tariffs

- Results suggest that tariff increases have an adverse impact on output and productivity; these effects are economically and statistically significant. They are magnified when tariffs are used during expansions, for advanced economies, and when tariffs go up.[1]

- Higher tariffs lead to an increase in inflation after two years. Furthermore, the effect on inflation is stronger during economic expansions than in recessions because of central banks respond with a contractionary impulse.

- Tariff increases lead to more unemployment and higher inequality, further adding to the deadweight losses of tariffs.

- Tariffs have only small effects on the trade balance though, in part because they induce offsetting exchange rate appreciations.

- Protectionism also leads to a decline in consumption; this, together with our other findings, suggests that tariffs are bad for welfare.

Relevant Developments

United States

May 14, 2024

[2] The US resident is directing increases in tariffs across strategic sectors such as steel and aluminum, semiconductors, electric vehicles, batteries, critical minerals, solar cells, ship-to-shore cranes, and medical products.

- The tariff rate on certain steel and aluminum products under Section 301 will increase from 0–7.5% to 25% in 2024.

- The tariff rate on semiconductors will increase from 25% to 50% by 2025.

- The tariff rate on electric vehicles under Section 301 will increase from 25% to 100% in 2024.

- The tariff rate on lithium-ion EV batteries will increase from 7.5%% to 25% in 2024, while the tariff rate on lithium-ion non-EV batteries will increase from 7.5% to 25% in 2026. The tariff rate on battery parts will increase from 7.5% to 25% in 2024.

- The tariff rate on solar cells (whether or not assembled into modules) will increase from 25% to 50% in 2024.

- The tariff rate on ship-to-shore cranes will increase from 0% to 25% in 2024.

- The tariff rates on syringes and needles will increase from 0% to 50% in 2024. For certain personal protective equipment (PPE), including certain respirators and face masks, the tariff rates will increase from 0–7.5% to 25% in 2024. Tariffs on rubber medical and surgical gloves will increase from 7.5% to 25% in 2026.

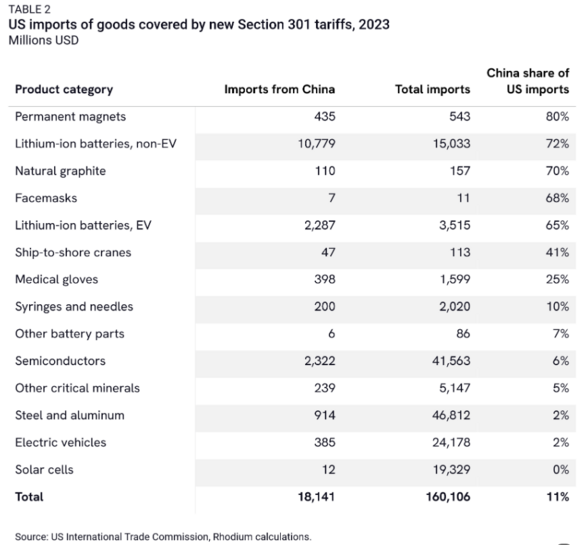

The amount of imports from China covered by the new tariffs, including EVs, is small at $18 billion.[3]

On May 22, USTR published the list of trade codes subject to increased tariffs. In 2023, the US imported $18.1 billion worth of these goods (see Figure 1). The largest product category is non-EV lithium-ion batteries ($10.8 billion, 59% of total), followed by semiconductors ($2.32 billion, 12.8% of total) and lithium-ion batteries for EVs ($2.29 billion, 12.6% of total).

Europe

March 6, 2024

The European Commission, the EU executive’s arm, said this week it has found “sufficient evidence” that the imports of new battery electric vehicles from China received subsidies including direct transfer of funds, tax breaks, or public provision of good or services below market prices.[4]

As a result, the commission has instructed customs authorities to start registering the import of the electric vehicles from China so they may be subject to the countervailing duties decided at the end of the investigation retroactively from this date to repair the injury already caused.

The EU inquiry doesn’t name specific producers, but the probe will focus on all manufacturers in China that export to the EU, including Tesla and major Chinese brands such as BYD Co., SAIC Motor Corp. and Nio Inc.

October 4, 2023

On October 4, 2023, the European Commission launched an anti-subsidy investigation into imports of passenger battery electric vehicles (BEVs) made in China. [5] There are three main concerns informing the EU’s decision to open an investigation into imports of China-made BEVs: substantial Chinese state support to its electric vehicle industry, a rapid increase in cheap exports to Europe, and mounting over-capacity in China that could accelerate those exports.

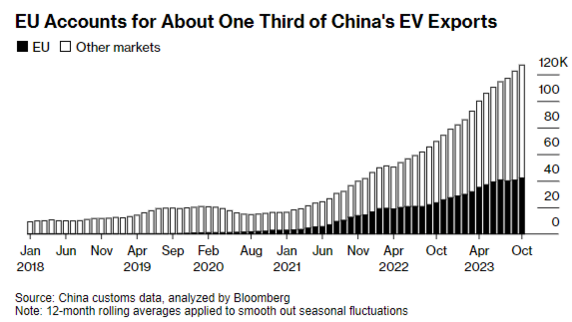

Trade data shows that China’s BEV exports have grown at lightning speed over the past three years (Figure 2). China’s share of global BEV exports grew from just 4% in 2020 to 21% in 2022, and China’s share of EU BEV demand grew from 4% to 16%. The Commission argues that rapidly rising Chinese exports of lower-priced BEVs (about 20% below European unit prices), and the sharp rise in China-based production capacity constitute an imminent threat to Europe’s auto industry.

In order to impose countervailing duties without running the risk of a major rebuke from national European courts (a more immediate threat than a WTO counter-case, which can take years), the Commission will need to prove three things: 1) that exporters of China-made cars received countervailable subsidies from the Chinese government, 2) that Europe’s industry is under imminent threat of injury, and 3) that there is a causal link between the two.

An early decision to impose duties might win favor in France, but it would likely rile other member states, chief among them Germany. Berlin has sent mixed signals about the probe, reflecting divisions within the coalition government. But there is significant concern in Germany that EU duties would trigger retaliation against its carmakers, which are deeply dependent on the Chinese market. France, on the other hand, has strongly supported the investigation, which it views as an opportunity to bring manufacturing jobs back and increase Europe’s resilience in green technologies.

The case of lithium-ion batteries

The battery sector has been a major recipient of Chinese state support over the past decade, resulting in rapidly falling prices and substantial overcapacity. In 2022, China’s production of lithium-ion batteries was 1.9 times the cumulative installed volume. Despite this, China’s support to the sector is still growing, with direct support mechanisms such as grants on the rise—even as those to BEV makers have come to plateau

However, there are two important differences between batteries and the other green tech sectors mentioned above, and these have implications for how the EU might respond. First, China’s dominance in the sector means that a trade investigation and resulting duties on China-made batteries could create major short-term inflationary pressures on downstream European industries, as alternative sources of supply are limited and more expensive. China today accounts for nearly half of global battery cell production, in addition to dominating the global market for processed battery components such as anodes, cathodes, electrolytes, and separators.

Second, Chinese battery makers have invested heavily in Europe, contributing to local economic activity and leading to an on-shoring of battery capacity—a form of de-risking, even if plants are Chinese-owned. It seems unlikely that the EU will take action against Chinese battery makers in the short- to medium-term, including through its new foreign subsidies instrument, which allows the EU to target subsidized production in Europe.

Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic’s combined market share reached 36% of EU battery demand in 2021, up from 7% in 2017, and largely driven by investment from South Korean companies Samsung, SK Innovation, and LG Energy. But that share has stagnated over the past two years, while the share of Chinese batteries in EU imports jumped to 46% in 2022, from 31% in 2021. This was largely due to price differences: in 2022, Chinese batteries were 33% cheaper than those produced in Europe.

China

May 21, 2024

References

- ↑ https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/WP/2019/wp1909.ashx

- ↑ https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2024/05/14/fact-sheet-president-biden-takes-action-to-protect-american-workers-and-businesses-from-chinas-unfair-trade-practices/#:~:text=The%20tariff%20rate%20on%20battery,zero%20to%2025%25%20in%202024.

- ↑ https://www.bruegel.org/analysis/rippling-out-bidens-tariffs-chinese-electric-vehicles-and-their-impact-europe

- ↑ https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-03-06/eu-moves-toward-hitting-china-with-tariffs-on-electric-vehicles

- ↑ https://rhg.com/research/opening-salvo-the-eus-electric-vehicle-probe-and-what-comes-next/